A Westmeath broadcaster has been collecting stories from people from Africa, Asia and South America about their memories of home.

"Home Stories" is a podcast series that offers insights into the lives, hopes and childhood memories of residents of Direct Provision and Emergency Accommodation in the midlands.

The writer and broadcaster Manchán Magan has spoken to new members of our community from Africa, Asia and South America about their favourite memories of home, their favourite foods and pastimes, and their hopes for the future.

Manchán Magan says, "Ireland is fortunate to have been gifted with this precious influx of people from a range of fascinating and exotic cultures in recent years. Most of them have fled some form of trauma and are currently making their way slowly through the Direct Provision system. These new members of our communities offer us a wonderful opportunity to get to know different parts of the world and different cultural practises that are often full of wisdom and new perspectives."

"Home Stories" is supported by Creative Ireland Laois and Creative Ireland Westmeath as part of the Creative Ireland Programme in partnership with Laois County Council.

The series containing interviews with Direct Provision residents from the Hibernian Hotel, Abbeyleix and the Montague Hotel, Emo was edited by Lauren Varian, with a soundtrack by Brían MacGloinn of Ye Vagabonds and Myles O'Reilly, and offers a series of evocative glimpses into the lives of refugees and asylum seekers who have fled to Ireland from persecution and danger.

Laois County Council Arts Officer and Creative Ireland Coordinator Muireann Ní Chonaill said, "When we first considered a project about the voices and lives of Direct Provision residents in Laois, we immediately thought of Manchán and were assured that his creative approach would be both sensitive to the needs and context of residents, as well as enabling chat and comhrá to engage with a myriad of themes close to the hearts and in the memories of our new community members. We're delighted that this podcast series is now being launched after delays due to Covid-19, and are so appreciative of the time given by Sandy/Charmaine, Noma, Lwandi and Feza from the Montague Hotel, Emo and Kemi, Aruna, Ivann, Sie and Pauline from the Hibernian Hotel, Abbeyleix. Special thanks also to Rosemary Kunene from Dignity Partnership, and Marina Rafter for their support with this project.

The Collinstown man has been speaking with Midlands 103's Sinead Hubble about the new series and says most of them fled some form of trauma and are currently making their way slowly through the Direct Provision system:

A resident of a direction provision centre in the midlands says Ireland has provided her with valuable educational opportunities.

Kemi, who grew up in rural Nigeria before moving to a city after her mother died when she was twelve, says people are always surprised she speaks English and operate modern devices.

The residents of Direct Provision centres in the midlands have been sharing an insight into their lives, hopes and childhood memories.

She has been speaking with Writer and broadcaster Manchán Magan about her culture and how girls will bend their knees when they meet elders in their community:

Oyeyemi, from the Yoruba tribe in southwestern Nigerian, shares insights into the traditional ifa faith, and would like to see more signs in Ireland of our traditional faith.

Oyeyemi is from the Yoruba tribe in southwestern Nigerian. 'To be a Yoruba is a thing to be proud of. We are ready to learn new things and open to new cultures.' Christianity and Islam are now the principal faiths, a traditional belief known as ifa, based on divination, is still practised. 'There's a god or iron, a god of thunder, a god of commerce, and also a god of the river and waters. I think we have the god of the forest too, that people worship and make sacrifices to.'

Each town will have a central altar, and people have smaller altars in their homes on which items like iron objects are placed for worship and blood sacrifices are made. Christian missionaries convinced the Yoruba that Christ had stronger magical powers than their gods and many converted, but

Oyeyemi says, 'In my own community there are still a mix of Christians and people who still practise pagan worship.' Both faiths emphasise honesty, sincerity and honourable practise. 'The ifa faith says you must look after nature. You should not cut down trees. You have to respect your environment. You don't farm with the intention of endangering another person.'

Oyeyemi is grateful for the role Irish priests played in Nigeria in 'getting people enlightened, educated, treated like human beings and also advising against old practices. With all due respect, these are the things that I'd like to see in Ireland again. I want to see the saints and scholars again. I want to see their influence on society.'

Oyeyemi been sharing his story with Manchán Magan:

Feza was raised near Lake Kivu in eastern Congo, swimming, hiking and occasionally going to see the mountain gorillas in the national park. He had to flee the warzone, but Ireland has now given him hope.

Feza, is from Bukavu in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where his mother, step-brothers and sisters still live. He has fond memories of 'my grandmother who used to cook beans mixed with cassava leaves and we'd have it with rice, and of the wonderful smoked fish from Lake Kivu.'

He used to love swimming in the lake and going to hike in Virunga National Park there the mountain gorillas live. 'We used to go in school holidays or on a Sunday. We'd organise a picnic... Seeing the gorillas was scary, but they are actually nice.' He hopes to return there, but 'up till now there is still violence. Women are being raped.'

He himself experienced traumatic events, but now 'in Ireland I have hope. Ireland has given me hope.'

He's been sharing his story with Manchán Magan:

Ivann is a teacher from Guatamala who had to flee because of the danger from drug cartels. He would love to teach Irish children about Mayan cultures and ways of respecting nature.

Ivann was born in Quetzaltenango, the second major city in Guatamala. His childhood was idyllic, 'We used to have picnics and go camping. We used to climb volcanoes. It was so amazing.' But all that changed when the drug cartels moved in. 'It's close to the border with Mexico and five or ten years ago terrorists with guns set up in the area with drugs and these kinds of things, and it changed everything, especially for the kids. Now it is very dangerous.'

His grandmother spoke the traditional Mayan languages K'iche' and Katchiqua. She mixed aspects of Christianity with Mayan practise. 'In springtime we used to pray to a god of rain to see how the corn was going to grow up in the land.' Ivann points out that Mayan beliefs differ from Christianity in that it recognises the power of nature rather than of the farmer. 'A Mayan god can be all of nature, or one tree, or a lake or mountain, or the clouds. The god is everywhere. When we see the mountains are green it means they reflect the life. When we see lakes or ocean, we give tribute to that, as a sign of gratitude for having water to drink.'

He was a teacher in Guatamala, as was his father and grandfather. 'I still have it in the blood. I miss my former students. But this is part of life. When the changes are coming no one is ever ready for them. I am still focused on trying to be a teacher here in Ireland, and maybe even teaching about Mayan culture or Spanish culture here. Since this country is doing so much for me why can't I contribute in return?'

He and his wife and children miss their old lives, but 'the most important thing is to feel safe. I'm happy to be here in Ireland now. We are building new lives here and are enjoying it. We hope to have a better future here.'

He's been sharing his story with Manchán Magan:

Sandra had to flee Zimbabwe for campaigning for women's rights, but fondly recalls an idyllic childhood of dancing, drumming and singing with all the local children. She wishes Irish people valued our language more.

Sandra was born in Zimbabwe, in a town 'where minimum-wage people stay'. She loved how everyone in the community felt like a sister or brother. Often there'd be up to fifty neighbouring children playing together - singing and dancing. 'If one family cooks they say come and eat to everyone. When you are sick you can call your neighbour and they will help you.' All the female elders were like mothers, aunties or grandmothers to her.

It surprises her how in Ireland people keep to themselves and she regrets that she must call people by their first names, and not just 'sister' or 'brother'. It's also surprising that people don't speak their native language. 'When you give birth to a child you speak to them in your language, then when they go to school they learn English but I find here the Irish language is slowly disappearing.'

She'd love to go home, but it's just not safe, as she was active in promoting women's rights and so was labelled dangerous. 'I am a poison in the country. We used to see our mothers being beaten up by the men. We formed a group to educate the girl child that she mustn't be abused. Opening those women's eyes. We were being beaten up, taken to jail, so that we don't teach the women these things.'

She's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

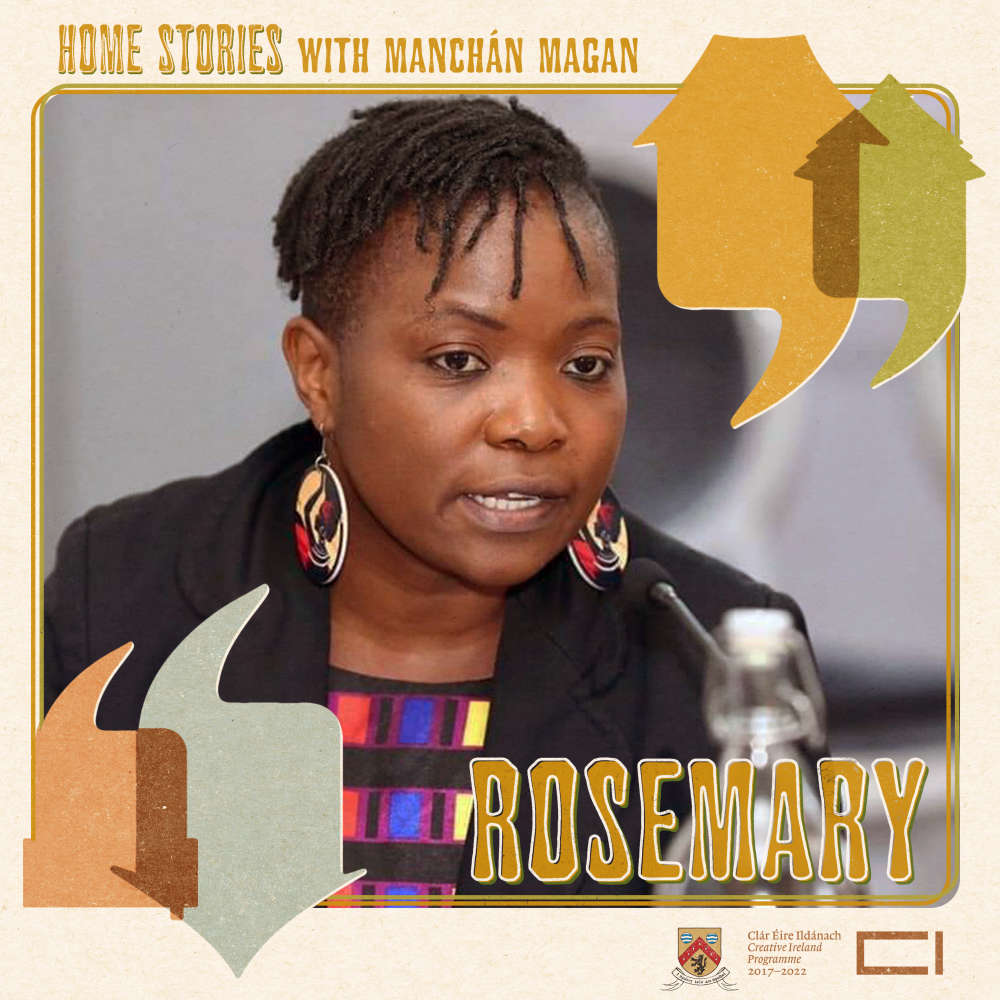

Rosemary was raised in her grandmother's mud and thatch cottage in Swaziland and educated in the university her father lectured in. She now runs a social enterprise helping Direct Provision residents in Ireland to set up in business.

Rosemary was born in Malawi, but then raised in Swaziland be her grandmother who was active in local politics. 'We had one house made of mud and thatched with grass, and another with brick and iron roof.' When she was a teenager she lived on college campus as her father was a lecturer and so she had friends from many different countries. 'After high school I wanted to work for myself. For me business is just part of my life. I love it.'

She runs a social enterprise in County Laois called Dignity Partnership. 'We encourage Direct Provision residents to get skills, or to set up in business. We help motivate them.' It arose out of a realisation that she had lost much of her own confidence when she was in Direct Provision and saw so many others suffering from trauma and undiagnosed depression and stress. 'We don't know what has happened to these people before they came to Ireland. A lot of them are traumatised and it manifests in different ways.' She herself still feels her heart pumping when the doorbell rings, thinking she's going to receive a letter saying she's being sent back. 'My goal is to expand the business and reach out to more people in Direct Provision.'

She's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

Adam, a barber in Athlone comes from a coastal town in Morocco famous for its fish barbecues. He misses home, but life isn't safe for him there anymore.

Adam comes from the coastal town of Safi in Morocco which he misses greatly, especially the seafood barbecues at every street corner and in people's gardens. 'Everyone in the city knows how to swim and how to fish, and the sardines we catch are famous throughout Morocco.' He tried cooking fish from the rivers around Athlone, but it's not the same.

He works in a barber shop in Athlone and has made good friends. He says the Irish are similar to Moroccans in that both are easy going and like to joke. The main difference is that 'the Irish get drunk while the Moroccans get stoned'. He'd love to go home, but life isn't safe for him there now and he realises that he might never get back. 'It's hard. After five years you miss your family a lot. I used not to think about it, but now I miss my mum. I see her getting older.'

Overall, he's adapting well to life in Westmeath, but he wishes people here would remember that most direct provision residents are entirely alone. 'Maybe if they try to get closer to us it's better. I have no family. When I go home I'm all alone.'

Pauline is a grandmother, originally from Rhodesia, who had to flee South Africa because of the violence. Moving her family to Ireland in the seventies was traumatic, but she's happy they are safe here.

Pauline grew up in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in a valley surrounded by enormous mountains. 'We grew up relatively poor, but happy. I remember my dad let us watch a python eat a dik-dik (small deer) and for seven days we returned to watch it as it lay there digesting. We only ate wild meat when we were growing up. My young brother started to hunt when he was four years old.'

She married in South Africa and now has five children and nine grandchildren. They lived outside Johannesburg on a plot, which is a small farm with different cottages on it. 'It was extremely dangerous. My husband was in twelve armed robberies, and we experienced four attempted high-jackings.'

She believes the Irish don't understand how violent South Africa really is. 'Horrible things happened to us there, especially to my daughter. It wasn't easy at my age to make this transition to Ireland, it was the hardest things we ever did, but now, I think, it was the best.'

She's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

Lwandise's family had a small farm in Zimbabwe with cattle, sheep and other animals. It was a polygamous family which meant there were always siblings to play with and mothers to care for him.

Lwandise comes from Matebeleland South in Zimbabwe, an area of dryland suitable for cattle ranching. His family had about twenty cattle and sheep, 'also we kept chickens, goats, and donkeys, and we grew grains so that we can feed our families throughout the year until the next rains. That's how we survived.' They also grew indigenous varieties of vegetable that could withstand the drought.

His father practised polygamy and so Lwandise had five siblings from his mother's side and twelve from his father's. Everyone was reared as part of the one family, 'boys have their own rooms and girls have theirs, regardless of which family. It was a very good way of being brought up.' The older wife chooses the next one, who will be able to help the first wife with her chores. 'They will build another hut for her, and when her children are older they can join the main family.' Among the advantages is that 'there is always someone in the house for you. There is always a mother. In the village the more you are as a family the healthier you are, the more you can do and the more you can produce.'

He misses life back home, but it's just not safe for him there. For his life in Ireland, he wishes that he be recognised 'regardless of my race or skin colour. That is my greatest hope.'

He's been sharing his story with Manchán Magan:

Sie comes from northern Zimbabwe where life involved fetching water, gathering firewood and long walks to school. She is now studying in UCC and is keen to become a mental health nurse.

Sie comes from a village without electricity in northern Zimbabwe where life involved walking long distances to fetch firewood and water, and hiking 6km to school each day through the bush. 'The good thing about the village is it teaches you your culture, values, and a sense of belonging.'

She has fond memories of gathering worms from mopani trees, which the family dried, then later boiled and fried as nutritious snacks. 'Also, I remember going to wash clothes in the river with my mother, then drying them in the sand, as she plaited my hair.'

She's keen to pass on the values of village life to her children here. They can be summed up by the Zulu phrase Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (a person is a person through other people). 'It means always being kind, loving other people as you would love yourself. What you do for others represents who you are.'

When she first arrived in Abbeyleix the first thing she saw were cows and sheep, 'so I was thinking, now we are going back to the village, what is happening?' Since then she has learnt to enjoy rural Irish life: 'people still talk to each other here. They ask about where I come from. I really appreciate that.'

She is currently studying mental health at UCC. 'This is not something we knew about when I was growing up. At home a person with depression is treated as an outcast, as irrelevant. I am beginning to understand more about my feelings. I am learning how to handle them. It's a skill that I can pass on to my children. I'd love to try mental health nursing.'

She's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

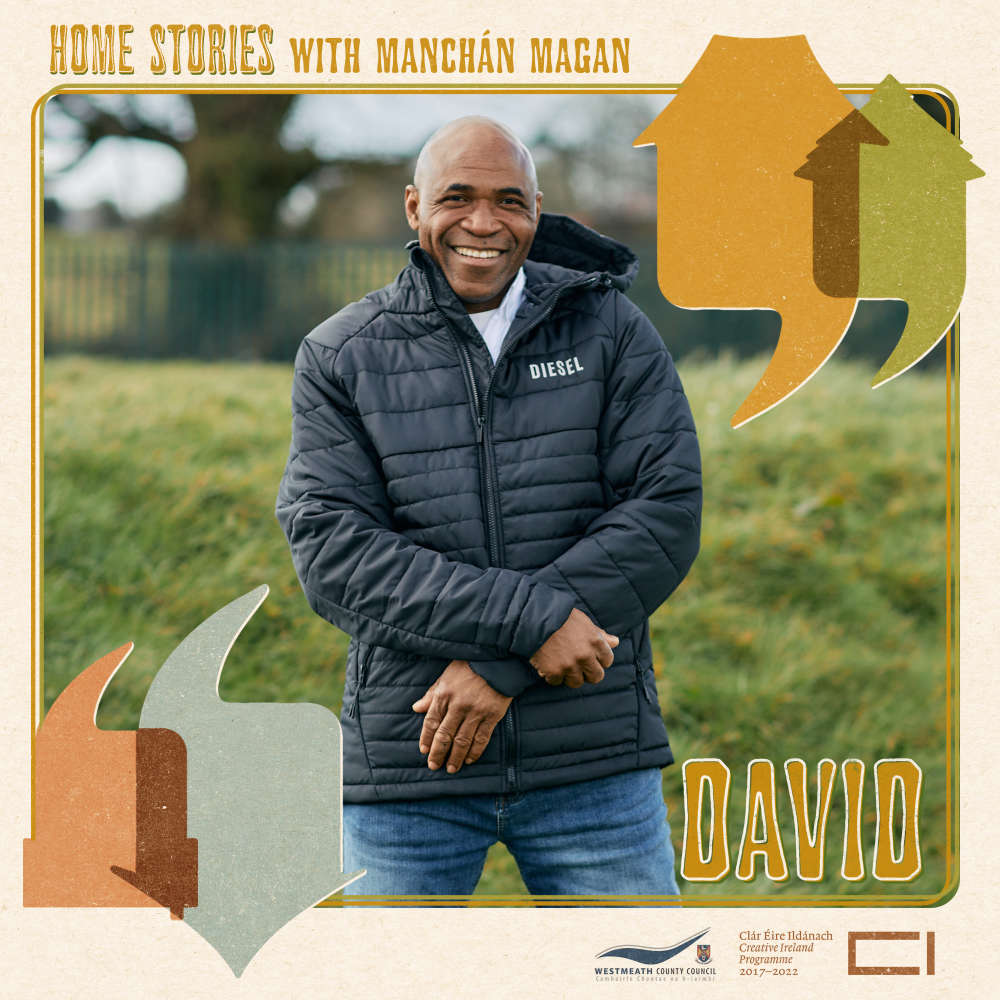

David grew up in a large polygamous family in South Africa which offered stability and care when his mother died young. He was a thatcher and also farmed cattle and vegetables.

David grew up in a large polygamous family in Lompopo province, South Africa. 'These kinds of families are most valued because one man if he is able to marry ten wives or even fifteen he still manages that everyone who belongs to that family feels well secured.' It creates a stable family environment. 'You wouldn't find any of those wives divorcing. My mother was number six for my father and she was the only one who couldn't have many kids. We were just three and my two sisters passed away. She also passed away at the earliest stage, when I was three, so I didn't get to enjoy her mothering me.'

He went to live with his uncle who had five wives, and who wanted him to attend school only three days a week and to herd his cattle the other days. 'I would milk almost 30 cows. I used to plough too. In wintertime I'd plant so many vegetables that the whole village would enjoy eating it.'

He enjoyed undergoing the various rituals of manhood, except circumcision: 'That was the most hard thing, but that pain doesn't last too long. And when you go back home the whole village will stand on their feet and they will slaughter cows and have a big celebration that lasts many weeks. And your name will be changed. You get a name not from your parents, but from how you feel and how you are.'

He then trained as a thatcher. 'I can thatch a house that will last perfectly for more than 30 years. I thatched my first house and it looked so beautiful and everyone was asking me to come thatch for them. That made me some money while I was a student.'

In the Direct Provision centre in Athlone he tends a vegetable patch. 'It gives me peace. Some people laugh at you as though you are a fool, but when they see the fruits of what you are doing, oh, you become a genius to them. You are more than a man. That's how I realised never do what is not in your heart. It will never give you peace.'

He's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

Tending to the garden at the direct provision centre in Athlone is David - whose family are descended from kings and, for that reason, were often asked to give advice and judgement in resolving local conflicts.

He was born in Lompopo province, South Africa, and later worked alongside Nelson Madela in community development.

. He is now studying social studies in Westmeath and is keen to be of service here.

He was born in Lompopo province, South Africa into a family that was descended from kings and so people would regularly seek guidance and justice from his father and uncle. They would listen quietly and patiently to all sides before delivering a judgment. 'Everyone must come to a point where they compromise. When this is implemented, the results are wonderful. They transform the entire community to good from bad.'

Having worked alongside Mandela at conferences with the ANC, David's passion is community development and conflict resolution, 'If Irish people want to know me they ought to give me a task that involves uniting people. It's a gift I have, to talk to people who have been fighting and killing each other.'

He is now studying social studies in Westmeath, and is keen to work in the community where he can be of service. 'I wish God sends me somewhere where there is huge need, so that I can make impact among the poorest people. I hope that I can identify something that will be able to bring a change for them even if they are no resources.'

He has never been as happy and secure as he is in Ireland. 'I am finding my voice, my role, here. I am willing and ready to be tested for any event, as long as there are people, no matter what the difficulties between them I can help bring them together.'

He's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

Naledi was reared by her grandmother in Botswana.

She studied business in Ireland until the school closed and she became pregnant.

She is keen to set up her own business, while continuing to work as a home-help for the elderly.

Naledi was reared by her grandmother in Francistown, Botswana, while her mother was in university. She had always longed to live in a city, 'but now having been in Ireland so long I started longing for village life where it was just so easy, where everything wasn't modernised, computerised.

It was a happy life. We'd tell tales, sitting by the fire.'

She is keen to teach her children about Botswana culture and her traditional language, and then let them decide whether they want to study it further or not.

She always wanted to work with people 'which is why I decided to be a healthcare assistant, to assist people who cannot assist themselves.'

She explains that a lot of refugees work in elder care because jobs are limited for foreigners and this is one of the few fields that have openings. 'Everywhere I went I realised I couldn't do what I wanted because I didn't have the qualifications or documentation. You end up settling. For me it was okay, as I always wanted to work with people.'

She worries about becoming institutionalised in the direction provision care system, 'Every day I'm in here I feel like I need to get out as the more you stay in a society where there is a certain way or limitation the more you are going to succumb to that and follow that trend.'

She's been sharing her story with Manchán Magan:

2026 Tullamore Tradfest To Take Place In March

2026 Tullamore Tradfest To Take Place In March

The True Origins Of Nollaig na mBan In Ireland

The True Origins Of Nollaig na mBan In Ireland

Rose Of Tralee Makes Blossoming Start To Dancing With The Stars

Rose Of Tralee Makes Blossoming Start To Dancing With The Stars

Offaly Acts Set To Feature As New Year's Festival Celebrations Kick Off

Offaly Acts Set To Feature As New Year's Festival Celebrations Kick Off

Rían, Jack, Emily And Grace Top Midlands 2025 Baby Names List

Rían, Jack, Emily And Grace Top Midlands 2025 Baby Names List

Wellness Soul Circle Coming To The Midlands

Wellness Soul Circle Coming To The Midlands

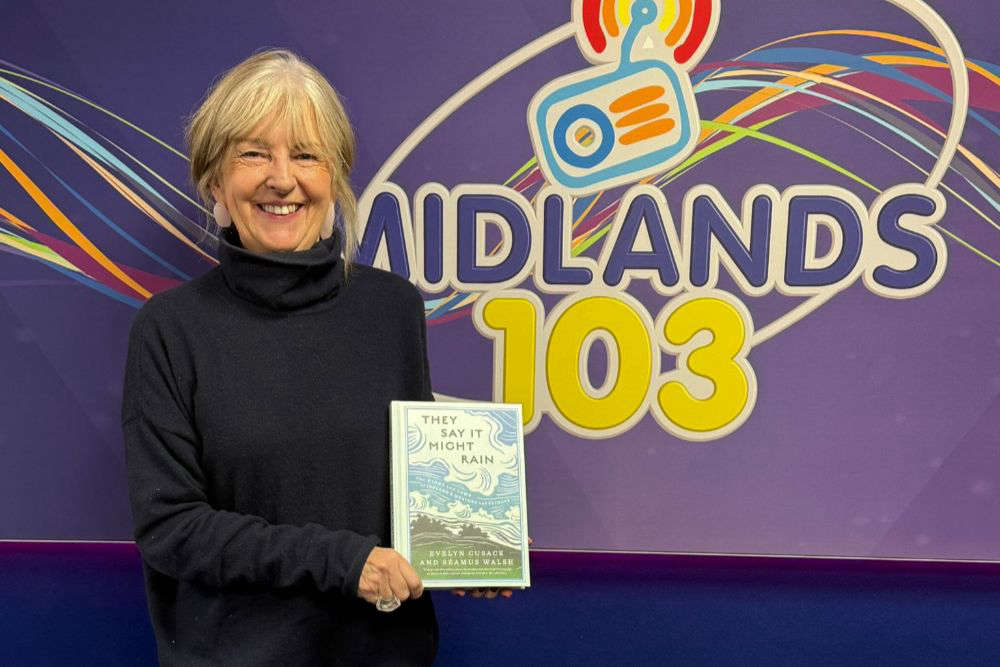

Retired Laois Met Eireann Forecaster Releases Book

Retired Laois Met Eireann Forecaster Releases Book

Electric Picnic Highlights Set For Our TV Screens

Electric Picnic Highlights Set For Our TV Screens

Laois Music Author Pays Tribute to Chris Rea

Laois Music Author Pays Tribute to Chris Rea

Offaly Woman Abroad Reflects On Australian Christmas Experience

Offaly Woman Abroad Reflects On Australian Christmas Experience

Westmeath Sports Clubs Do 12 Laps of Christmas

Westmeath Sports Clubs Do 12 Laps of Christmas

Westmeath Psychotherapist Advises Caution On Naughty Or Nice List

Westmeath Psychotherapist Advises Caution On Naughty Or Nice List

New Programme For Laois And Offaly TY Students In Digital Arts

New Programme For Laois And Offaly TY Students In Digital Arts

Coillte Opens Applications for 2026 Forestry Scholarship

Coillte Opens Applications for 2026 Forestry Scholarship

Offaly Choir Bringing Festive Cheer To Church This Weekend

Offaly Choir Bringing Festive Cheer To Church This Weekend

Midlands County Hosts Water Safety Awards Ceremony

Midlands County Hosts Water Safety Awards Ceremony

Look back on Forest Fest 2024

Look back on Forest Fest 2024