Chelsea Brereton said she left the hospital “broken, confused and consumed with grief"

A Kildare woman has told an inquest that she believed her stillborn son would still be alive if she had received proper care by medical staff at the Midlands Regional Hospital in Portlaoise during her pregnancy.

Chelsea Brereton gave evidence at a sitting of Laois Coroners Court that she left the hospital “broken, confused and consumed with grief,” on April 15, 2020 after being informed that her baby boy was dead in her womb.

“It was the worst day of my life that I’ve replayed in my head for five years,” said Ms Brereton.

Her son, Mason, was delivered stillborn the following day. Ms Brereton, who comes from Sallins, Co Kildare, gave evidence that was highly critical of the treatment she received at the hospital in Portlaoise as well as the fact that her baby’s organs were retained after a postmortem against the express instructions of her and her partner, Jamie Dunne.

The inquest heard she was discharged “in agony and overwhelmed with anxiety” from the hospital five days before learning her son had died in her womb at a time she had “begged” for labour to be induced.

A pathologist, John Gillan, said a postmortem showed the baby died as a result of a lack of oxygen caused due to hyper-coiling of a short umbilical cord.

Dr Gillan estimated that death occurred no more than 48 hours before the lack of the foetal heartbeat was detected. The family’s counsel, Sara Antoniotti SC, noted that the patient would have received regular monitoring that would have picked up a problem with the foetus if she had not been discharged on April 10, 2020.

Ms Antoniotti said guidelines had been breached by Ms Brereton being discharged without any medical review and against her maternity plan.

Recording a narrative verdict, the coroner Eugene O’Connor said he would also propose detailed recommendations at a later stage in relation to procedures governing postmortems and training.

Some relatives of the deceased, whose family had sought a verdict of medical misadventure, walked out angrily from the inquest on hearing Mr O’Connor’s ruling.

The coroner observed that there had been “some shortcomings” in the care of Ms Brereton and noted she had “a difficult experience with a difficult pregnancy.”

He claimed there was also a need for an update “with some urgency” of the guidelines regarding the induction of labour.

The coroner heard there was a conflict of evidence between Ms Brereton and hospital staff over aspects of her care including whether she was offered a cervical sweep to induce labour.

Counsel for the hospital, Conor Halpin SC, suggested the patient had a “flawed recollection” about being in agony when she was discharged on April 10, 2020 already past her due delivery date.

The inquest heard evidence from hospital witnesses that there was no concern about discharging Ms Brereton as she was not experiencing any bleeding, contractions or reduced foetal movements.

However, Ms Brereton said: “I was in excruciating pain. I was begging for help and all I got was paracetamol.”

Asked by Mr Halpin if she had medical qualifications, she replied: “No but I know my body better than anyone else.”

Ms Brereton said she was discharged without being examined by a consultant despite experiencing contractions every five minutes and told repeatedly that she was not to return to the hospital until she was in active labour.

Consultant gynaecologist, Shoba Singh, gave evidence that she had not checked the patient’s medical history before discharging her and was also unaware of the baby’s foetal movements. T

he inquest heard Ms Brereton returned to the hospital on April 15, 2020 when she did not feel much movement with her baby.

Ms Brereton claimed Dr Singh came into a room abruptly and spoke over her about the result of a scan and “cold as ice said: ‘It’s dead. No heartbeat.’”

She recalled feeling her own heart stop and starting screaming while her partner was waiting outside “with no idea of the horror unfolding.”

However, she claimed the consultant just scoffed and remarked: “It’s dead. There is nothing I can do.”

Ms Brereton said Dr Singh went “absolutely mental” when she told her partner to come into the hospital and called her “a silly girl” instead of explaining what had happened.

She disputed as “false” medical records which stated that the couple were offered condolences and allowed time and space to grieve.

She accused Dr Singh of being “very cold and distant” and whose only concern was to get herself and her family to leave the hospital as soon as possible.

“Nobody should ever have to find their baby died by being told that ‘it’s dead,’” she told Mr Halpin.

“It just totally dehumanised him and made an already difficult situation so much worse,” she observed.

“To this day, I am still grieving my son, who I believe would be here with me today if I had received the care we both deserved,” said Ms Brereton.

She also criticised being asked to attend the hospital after Mason’s death during antenatal clinic hours where she was surrounded by pregnant women and new mothers with healthy babies.

“I cannot put into words how difficult this was for me, mentally and emotionally,” she added.

Ms Brereton said the hospital never seemed to realise how heartless and inconsiderate that was.

The inquest heard she became pregnant with her daughter, Kayla, while she was still waiting to get answers to questions about her son’s death from the hospital in Portlaoise.

She told the hearing that the change in care she experienced while attending the National Maternity Hospital in Holles Street, Dublin for her second pregnancy was “astonishing.”

Ms Brereton said both Kayla and another daughter, Emily, were born alive and healthy in Holles Street.

“It is my strong belief that if the Midland Regional Hospital in Portlaoise had acted in the same manner as the National Maternity Hospital, Holles Street that my son would have been born alive and healthy and I would have him in my arms today,” she observed.

Ms Brereton said nobody explained to them the findings of a postmortem on Mason’s body which they received 19 months after his death.

She told the hearing that it was “absolutely soul-breaking” to have to research the findings via Google.

A month later, Ms Brereton was “hysterical” when the couple were told that Mason’s brain, left lung and intestines had been retained despite their express instructions that their baby’s organs should not be retained under any circumstances.

Ms Brereton said they had to open their son’s grave a second time and see his little coffin in the ground five days before Christmas.

In evidence, Dr Gillan said he was never aware about the request for the baby’s organs not to be retained but stressed they were required for very exhaustive examinations of an unexpected and unexplained death.

The pathologist described the long delay in returning Mason’s body parts to his family as “a fiasco” which was “highly regrettable.”

Dr Gillan told the inquest that he had not been able to examine the organs for over a year after the baby’s death due to an exceedingly high workload.

He attributed the failure to inform Mason’s family about the retention of the organs due to the departure of a specialist laboratory technician and “mismanagement.”

However, Dr Gillan said there was now a register in place relating to any retention of organs.

Following the inquest, Ms Brereton said nothing would bring their beautiful son back but the verdict has to result in the Midland Regional Hospital in Portlaoise and the HSE “learning from their mistakes.”

“We need to fully inform maternity care in our country. Policies need to be put in place and actually implemented to ensure no other families are destroyed like ours,” she added.

'One Final Push' - Mental Health Charity In Laois Appeals To Public For Funding

'One Final Push' - Mental Health Charity In Laois Appeals To Public For Funding

Pay-Related Changes To Social Welfare Payments Come Into Effect Across Midlands Today

Pay-Related Changes To Social Welfare Payments Come Into Effect Across Midlands Today

HSA To Begin National Farm Safety Inspection Today

HSA To Begin National Farm Safety Inspection Today

Revenue Officers Seize Over €235k Of Cash In Midlands And Sligo

Revenue Officers Seize Over €235k Of Cash In Midlands And Sligo

Midlands Man Who Died Following Road Crash To Be Laid To Rest Today

Midlands Man Who Died Following Road Crash To Be Laid To Rest Today

SIPTU Members Bord Na Mona Recycling Strike Called Off

SIPTU Members Bord Na Mona Recycling Strike Called Off

Offaly Auctioneer Feels Landlords Need To Be Included More in Rent Discussions

Offaly Auctioneer Feels Landlords Need To Be Included More in Rent Discussions

"Litter Picking Party" Taking Place Tomorrow On Westmeath Bog

"Litter Picking Party" Taking Place Tomorrow On Westmeath Bog

€2.5 Million Euro In National Roads Funding Going To N4 Mullingar to Rooskey Project

€2.5 Million Euro In National Roads Funding Going To N4 Mullingar to Rooskey Project

Midlands Man Killed In Westmeath Crash Remembered As "Hard Working" And "Unassuming"

Midlands Man Killed In Westmeath Crash Remembered As "Hard Working" And "Unassuming"

Midlands Sees Homelessness Surge

Midlands Sees Homelessness Surge

Chappell Roan and Hozier Added To Electric Picnic Lineup

Chappell Roan and Hozier Added To Electric Picnic Lineup

Midlands MEP Says Any US Pharma Tariffs Will Mean Gradual Effect On Ireland

Midlands MEP Says Any US Pharma Tariffs Will Mean Gradual Effect On Ireland

"Almost Beyond Belief" Longford Westmeath TD Assessment Of CAMHS Services

"Almost Beyond Belief" Longford Westmeath TD Assessment Of CAMHS Services

Offaly Arts Centre To Host Official Launch Of BIOPHILIA Art Experience

Offaly Arts Centre To Host Official Launch Of BIOPHILIA Art Experience

Offaly Family Celebrates Irish Cancer Society's Support On Daffodil Day

Offaly Family Celebrates Irish Cancer Society's Support On Daffodil Day

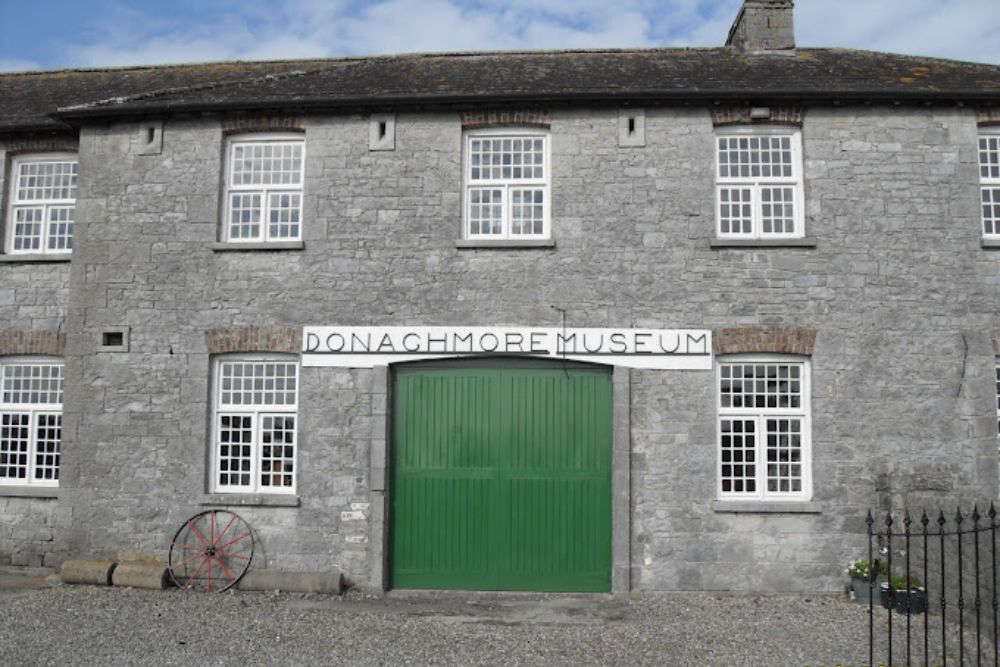

Historic Midlands Structures Get €500k

Historic Midlands Structures Get €500k

Gardaí Issue Public Appeal After Fatal Westmeath Crash

Gardaí Issue Public Appeal After Fatal Westmeath Crash

Offaly Mother Stresses Importance of Parents Associations

Offaly Mother Stresses Importance of Parents Associations

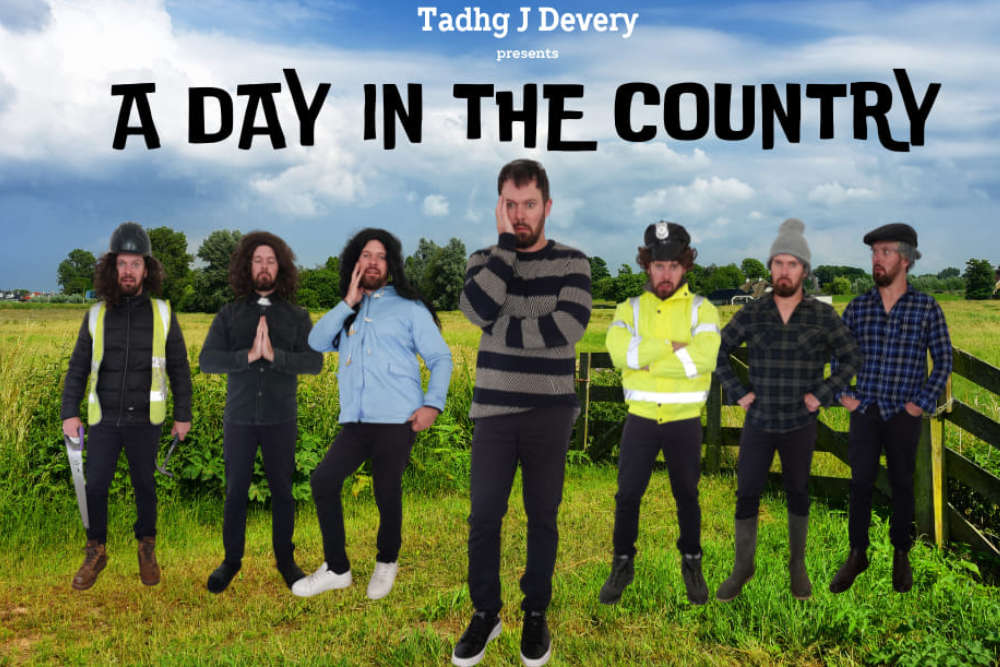

Offaly Comedian Bringing 'Village Of Characters' With Him On Tour

Offaly Comedian Bringing 'Village Of Characters' With Him On Tour